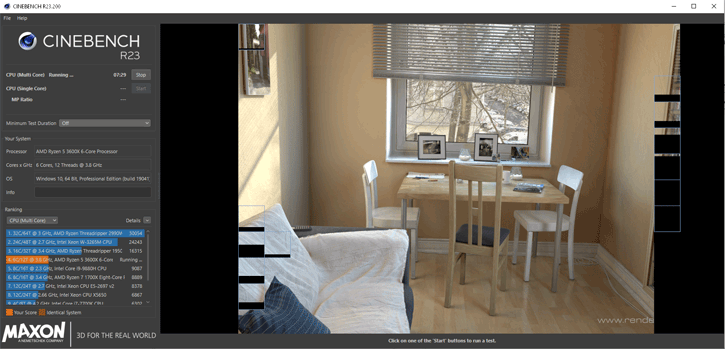

Cinebench measures CPU rendering performance with simple, repeatable tests. I’ve used it to compare chips, spot thermal throttling, and check sustained performance — honestly, it’s one of the first tools I reach for when validating a build.

Want the short version? It runs on Windows and macOS, uses Cinema 4D’s render engine, and gives point scores (higher = faster). It’s straightforward, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. There are exceptions and caveats depending on your niche.

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Developer | Maxon Computer GmbH |

| Release date | June 2021 (Cinebench R23). Still supported in 2025. |

| Type | CPU benchmark (rendering) |

| License | Freeware |

| Purpose | Measure CPU speed while rendering with Cinema 4D engine |

| Rendering engine | Cinema 4D Release 23 (render-focused) |

| Test types | Single-core, multi-core, optional 10‑minute stress run |

| Min test time | 10 minutes for valid sustained scores |

| Score system | Points-based (higher is better) |

| OS | Windows 10/11 (64-bit) and macOS 10.13.6 or newer (Apple Silicon supported) |

| Reqs | 64-bit CPU, ~4 GB RAM minimum, SSE3 support, ~200 MB disk |

| Key features | Real render scene, sustained performance, thermal throttling detection, online score comparison |

| Compared to R20 | Longer tests, better thermal insight, Apple Silicon support, updated render code |

| Use cases | CPU comparison, stability checks, overclock validation, thermal testing, reviews |

| File size | ~180–250 MB depending on platform |

| Availability | Free from Maxon and the Microsoft Store |

| Online ranking | Scores can be uploaded and compared on Maxon’s database |

| Limitations | CPU-only, focused on Cinema 4D rendering scenarios, long run-time for validated scores |

Here’s the funny part: many people treat Cinebench like a single truth. That’s controversial, I know. In my experience, a high Cinebench score usually means strong rendering throughput, but it won’t always translate to faster video exports or better gaming performance — different workflows stress different parts of the CPU. To be fair, this doesn’t always work the way you expect.

So, when should you rely on it? If you need to check sustained multi-core performance or compare cooling and power limits between systems, it’s reliable. Want single-thread latency? Use it for that too. Want GPU metrics? It won’t help (use a GPU bench instead).

- Practical tip: run the 10‑minute test to catch throttling.

- Pro tip: test at stock and with your intended power profile — results change fast.

- Compare like with like: same OS build, same background tasks.

Run repeatable tests. Scores mean little unless you control variables — same firmware, same cooling, same OS state.

Quick commands to check CPU cores (so you know what you’re testing):

REM Windows

wmic cpu get NumberOfCores,NumberOfLogicalProcessors

# macOS

sysctl -n hw.ncpu

Why follow these steps? Because the score is only useful relative to a known system state. If you don’t control variables, numbers lie. (They really do.)

Oddly enough, a counterintuitive point: a chip with lower multicore score can feel snappier in daily apps if it has better single-core turbo or faster memory latency. Think of Cinebench as a dyno for engines — it shows peak torque under a defined load, not how smooth the ride is on city streets.

Between us, some reviewers chase headline scores and forget real workloads. That’s frustrating! But you can use Cinebench properly and save money when choosing parts.

One more caveat: results depend on OS updates, drivers, and firmware. Test after firmware changes. Test after major OS updates (for example, after an update on 14 April 2025 you might see different behavior).

Final quick checklist — copy this:

- Clean boot (minimal background apps).

- Run 10‑minute stress for sustained score.

- Record thermals and frequencies while testing.

- Compare results on Maxon’s online database.

Surprisingly useful, imperfect tool. Use it with context, and you’ll make better decisions. It works — mostly. Try it. Test twice!